Among all the strange objects in libraries and museums, few are as unsettling as anthropodermic books. These are volumes bound in human skin, sitting quietly on shelves beside far more ordinary tomes. For readers who love the macabre side of book history, they represent the point where literature, medicine and mortality collide in a truly disquieting way.

What exactly are anthropodermic books?

In simple terms, anthropodermic books are any books whose bindings are made from human skin. Most surviving examples are not occult grimoires or forbidden spellbooks, but medical texts, legal documents or personal memoirs. Many were created in the 18th and 19th centuries, often by doctors with access to cadavers, or by institutions connected with prisons and hospitals.

The practice was never mainstream, but it was also not as vanishingly rare as many people assume. For a long time, stories about such bindings were passed on as hushed rumours by librarians and curators. Only recently have scientific tools like peptide mass fingerprinting been used to test bindings and confirm which ones are truly human and which are simply morbid legends.

Gruesome materials lurking in library stacks

Human skin is only the most shocking entry in a long list of unsettling binding materials. Early modern bookbinders were disturbingly inventive. Vellum made from calf, goat or sheep was standard, but there are documented bindings using pigskin, horsehide and even fish skin. Some devotional books were wrapped in the tanned hides of sacrificial animals, chosen for their religious symbolism.

Collectors with darker tastes occasionally commissioned bindings from the skins of executed criminals, hoping that the book itself would become an object lesson in justice. Others used the skin of loved ones, turning grief into a morbid attempt at memorial. In both cases, the book becomes a physical relic of a life, not just a container for words.

Beyond skin, there are books inlaid with human hair, teeth and bone. Victorian mourning albums sometimes used woven locks of hair to decorate covers and endpapers. In medical collections, one can find anatomical atlases with preserved tissue samples sealed into the pages, blurring the line between textbook and specimen jar.

The science behind identifying anthropodermic books

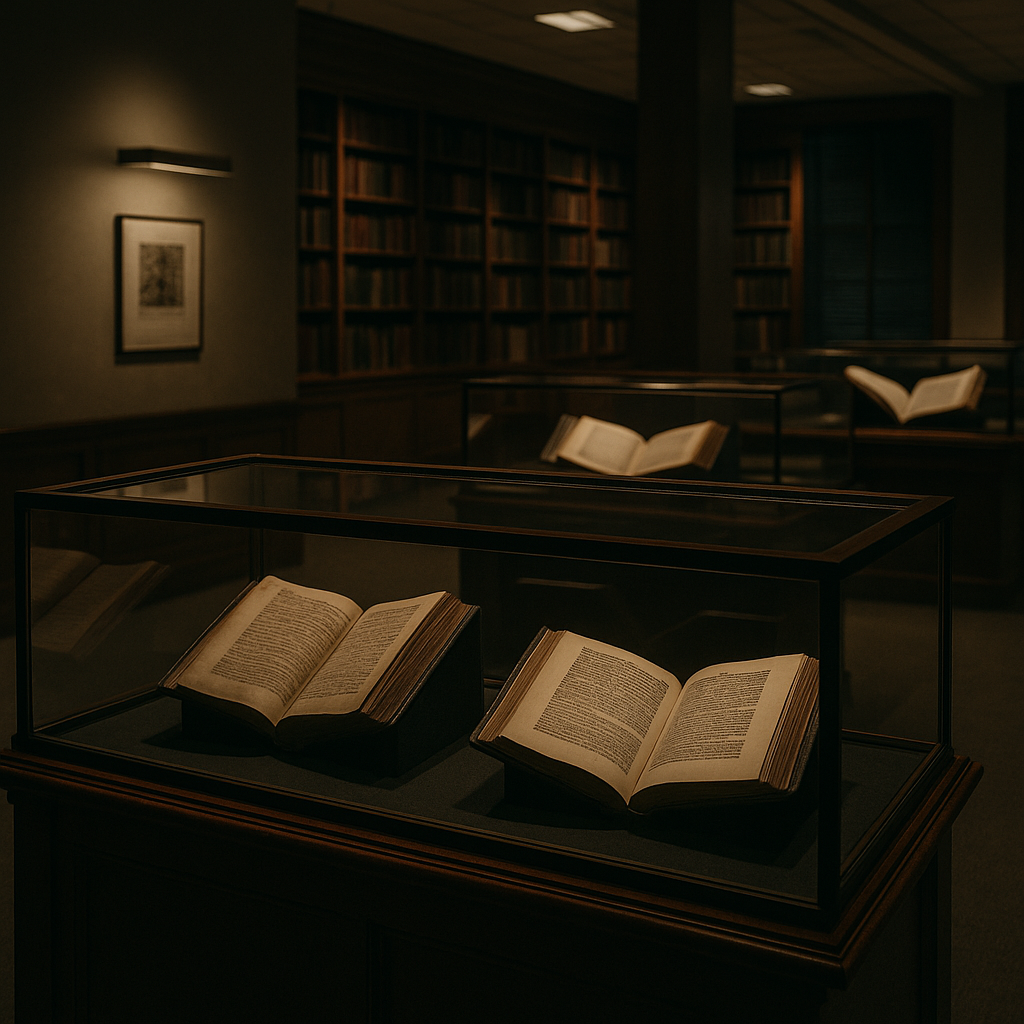

For years, librarians relied on handwritten notes, legends and wishful thinking to decide whether a volume counted as an example of anthropodermic books. Many bindings that were proudly displayed as human turned out, under scrutiny, to be ordinary pig or sheep leather. The modern push to verify these claims has transformed the field.

Today, researchers take tiny samples from bindings and analyse the proteins within them. Different species leave different molecular signatures, allowing scientists to distinguish between human and animal origins. This has quietly debunked a host of sensational claims while confirming a smaller, but still chilling, core of genuine examples.

Some of the most famous confirmed cases are held in university libraries, often attached to medical schools. A few are linked to notorious historical figures, such as executed murderers whose bodies were turned into both anatomical specimens and book covers. Others are more anonymous, their former owners or donors lost to time.

Ethics, consent and what to do with macabre books

The existence of these bindings raises uncomfortable questions. Were the people whose skin was used ever asked for consent? In most cases, the answer is almost certainly no. Many bodies came from prisons, workhouses or hospitals where the poor and marginalised had little control over what happened to them after death.

Modern institutions now debate whether to keep these books on open shelves, lock them away, or even deaccession them entirely. Some libraries frame them as teaching tools, using them to talk about the history of medical ethics, body rights and power. Others worry that displaying them risks turning human remains into morbid spectacles.

There is also the question of cataloguing. Do you label such a book plainly as being made from human skin, or soften the language to avoid distressing visitors? Different institutions have taken different approaches, but the trend is towards transparency and respectful handling, acknowledging the humanity of the person whose body became an object.

Leave a Reply